by Jamie Davies O’Leary

(September 14, 2018)

This month, PDK released results from the 50th annual poll of public attitudes about public schools. Conducted by Gallup and Phi Delta Kappa (PDK), the survey offers the most trusted source of opinion data on K-12 education issues ranging from school funding and teacher pay to safety and school day hours. Yet one topic rose to prominence this year: the dismal state of public opinion on the teaching profession.

This month, PDK released results from the 50th annual poll of public attitudes about public schools. Conducted by Gallup and Phi Delta Kappa (PDK), the survey offers the most trusted source of opinion data on K-12 education issues ranging from school funding and teacher pay to safety and school day hours. Yet one topic rose to prominence this year: the dismal state of public opinion on the teaching profession.

Along with survey results, PDK released a report whose title says everything on this alarming—though perhaps unsurprising—trend. “Teaching: Respect but dwindling appeal,” juxtaposes the public’s broad support for teachers with their opposing aspirations for their own kids. That is to say, although Americans have confidence in public school teachers and support them, we don’t want to be them. Or have our children be them. If that’s not a troubling degree of dissonance about our feelings towards those in the “noblest profession,” I don’t know what is.

Six in ten respondents said they had trust and confidence in public school teachers. Further, a significant majority seem to believe that teachers deserve better: 66% of respondents said that teachers were underpaid and 78% would support a strike to achieve better wages. (Somewhat surprisingly, this even played out across political party lines).

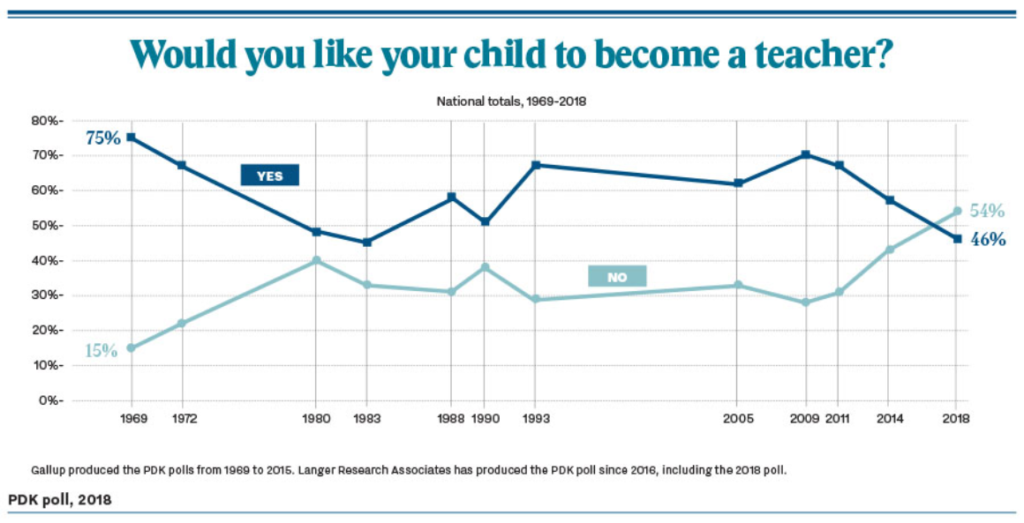

Yet less than half of respondents said they would want their own child to become a public school teacher—a record-low response to this question since PDK began the poll in 1969.

Figure 1: Public responses to PDK’s question about one’s own child becoming a teacher, 1969-2018

As a former public school teacher, a public school parent, and someone who’s dedicated a career to education practice or policy in some fashion, these results are discouraging in and of themselves.

As a former public school teacher, a public school parent, and someone who’s dedicated a career to education practice or policy in some fashion, these results are discouraging in and of themselves.

But my first thought in seeing the latest PDK poll—just moments after dropping my three-year old off at preschool—was this: If most Americans would counsel their own children away from the K-12 teaching profession, what does that say about those who care for and teach younger children, toddlers, and babies?

Salaries for childcare workers and preschool teachers are notoriously low, the benefits few, and the challenges many. There’s no doubt in my mind that a similar (or worse) opinion gap might emerge about those who teach and nurture children ages 0-5 years.

Oh, we love and appreciate our childcare providers and preschool teachers. Parents know better than anyone what they endure all day; the glue, spit-up, sunscreen, or sauce on their clothes are as varied as the range of expectations placed upon them. We recognize how skilled they are, having borrowed their tips on how to handle our child’s particular habit, having watched them encourage empathy, creatively resolve conflict, and deliver a mean read-aloud—practically all at the same time.

Yet their compensation does neither reflect the expertise we demand of them, nor the immense amount of hope we place in them to shape children during their most malleable years. This is bad news for all of us, parents or not. It’s true nationally and even more dire in Ohio, as a glance at wage data for childcare workers and preschool teachers will attest.

Table 1: Annual Mean Salary Data, Early Learning v. Elementary Teachers

| National Median | Ohio | % Below the National Median | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Care Workers | $23,760 | $22,510 | -5.3% |

| Preschool Teachers | $33,590 | $27,720 | -17.5% |

| Kindergarten Teachers | $57,110 | $56,400 | -1.2% |

| Elementary School Teachers | $60,830 | $59,950 | -1.4% |

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2017. Note, annual median salary figures for the above teaching positions does not include special education teachers.

As Table 1 shows, wages for all early care, kindergarten and elementary school teachers in Ohio fall below the national median, with preschool wages especially low. The Buckeye State ranks 24th lowest for childcare workers and 8th lowest for preschool teachers, with the average preschool teacher earning just 49% of the annual salary of the average kindergarten teacher.

Viewing the hourly wage averages for childcare workers in Ohio is another way to illustrate how abysmally they are compensated, especially in the context of a statewide Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS) meant to improve the quality of care and demand more from teachers.

Table 2 shows, those caring for Ohio’s youngest children are most similar in compensation to dry-cleaning workers and those working in food preparation (note: these figures do not include preschool teachers).

Table 2: Mean hourly wages for Ohio workers near or on par with childcare workers (2017)

| Cooks, Short Order | 10.43 |

| Bartenders | 10.46 |

| Home Health Aides | 10.51 |

| Food Servers, Nonrestaurant | 10.51 |

| Food Preparation and Serving Related Workers, All Other | 10.53 |

| Maids and Housekeeping Cleaners | 10.63 |

| Food Preparation Workers | 10.66 |

| Waiters and Waitresses | 10.67 |

| Parking Lot Attendants | 10.67 |

| Pressers, Textile, Garment, and Related Materials | 10.68 |

| Laundry and Dry-Cleaning Workers | 10.70 |

| Childcare Workers | 10.82 |

| Food Preparation and Serving Related Occupations | 10.83 |

| Cooks, All Other | 10.93 |

| Personal Care Aides | 10.93 |

| Personal Care and Service Workers, All Other | 11.01 |

| Locker Room, Coatroom, and Dressing Room Attendants | 11.08 |

| Door-to-Door Sales Workers, News and Street Vendors, and Related Workers | 11.17 |

| Nonfarm Animal Caretakers | 11.29 |

| Motion Picture Projectionists | 11.30 |

| Gaming Change Persons and Booth Cashiers | 11.59 |

| Taxi Drivers and Chauffeurs | 11.76 |

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2017

Most parents realize how important early childhood educators are and put a lot of faith in them. In a 2016 survey of parents and educators conducted by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), six in ten parents named teachers as an extremely important indicator of program quality—specifically, “teachers who inspire the kids.” In comparison, four in ten named parent engagement, a high QRIS rating, or small class size as extremely important.

Among educators surveyed by NAEYC, eight in ten said that “any major effort to increase the quality of early childhood education programs will fail unless early educators receive increased salaries and benefits.” Yet most states, including Ohio, are demanding quality improvements even while early care providers and preschool teachers earn less than half of what their kindergarten peer teachers earn.

None of this information is new or groundbreaking, but it’s critical to talk about.

Half of the nation’s early childhood educators are forced to rely on public assistance in order to survive, cashing in on food stamps and welfare while being unable to afford child care for their own children. Meanwhile, parents of all income ranges can scarcely afford childcare costs already. It’s a perfect storm, and it’s not going to go away without deliberate policy efforts and the political will and courage to sustain them.

No matter what you think about current federal or state spending habits, elevating teacher pay in the early childhood space will have to come at least in part from new public investments—be they federal, state, local, or combined. A 2018 Policy Matters brief casts Ohio’s spending on childcare $1.1 billion—no chump change, to be sure—70% of which is sourced from federal coffers.

Policy leaders might also consider ways to reduce costs for early care teachers. Housing subsidies, scholarships for extra training, or expanded student loan forgiveness programs could go a long way toward helping our children’s teachers stay financially afloat—and some of these initiatives could be driven locally.

Our nation’s respect for the teaching profession—whether K-12 teachers or those tasked with caring for the very youngest members of society—simply is not enough. The question remains: when will we decide as a society to stop idealizing teachers and put our money where our mouth is?