AUTHORS: Maria Abdul-Masih, M.S., Kelly M. Purtell, Ph.D. & Arya Ansari, Ph.D.

The COVID-19 pandemic deeply affected young children and families across the United States (Kuhfeld et al., 2022), with lasting effects that continue to shape the daily lives of children and families. The pandemic also worsened existing inequities in society, with families from low-income and marginalized communities being disproportionally affected (Perry et al., 2021). Economic insecurity, job loss, and disruptions to child care and education all contributed to these disparities (Gassman, Pines et al., 2020; Singletary et al., 2022).

Despite these challenges, programs like Early Head Start (EHS) can help reduce some of these inequities. EHS, a federally funded program created nearly 30 years ago, serves low-income families with infants and toddlers under three years of age. This program offers a range of services, including home visits, early childhood education, health and nutrition services, and family support and engagement. These services provided by EHS help families build more supportive home environments and provide children with a strong start in life (Love et al., 2005), which is critical for their future school success and well-being (Duncan et al., 2007).

Despite the known impacts of the pandemic and recovery efforts, there has been limited research on how these changes have specifically affected families involved in EHS. Accordingly, this research brief considers:

- changes in the characteristics of EHS families before and after the pandemic;

- the stress and well-being of families in EHS, and how this compares before and after COVID-19; and

- the extent to which families’ experiences with stress and well-being vary based on their demographic and household characteristics

DATA

We used data from two cohorts of the Early Head Start Family and Child Experiences Survey (Baby FACES), which is a nationally representative sample of children and families served by EHS. We used data from 2018 and 2022 to assess the stress and well-being of EHS families before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. This analysis included 2,826 children (birth through age 2) and their families in 2018, and 1,477 separate children and families in 2022. These children were recruited from EHS programs across the United States. In 2018, 54% of children received center-based services, 35% received home-based services, and 11% received a combination of both center- and home-based services. Rates are similar for the service type of children in 2022 (See Table 1). In 2018, caregivers were racially and ethnically diverse with 38% of respondents identifying as Hispanic, 29% identifying as Black, 28% identifying as white, and 6% identifying as another race, non-Hispanic. The sample was also linguistically diverse, with 56% of households reporting English as their primary language, 19% reporting another language as their primary language, and 24% identifying as multilingual households. The racial/ethnic and linguistic diversity was similar in 2022 (See Table 1). Additional descriptive information is provided in Table 1.

For this analysis, we focus on several aspects of stress and well-being that were reported by parents in 2018 and 2022, including reports of:

- financial strain: This six-item measure assessed whether families had enough money to afford the kind of home, medical care, clothing, and food they need, and if they had enough money to pay for bills and make ends meet. Scores on each item were summed so higher scores indicate greater economic pressure.

- parents’ depressive symptoms: This 20-item measure asked parents to rate how often statements such as, “I could not shake off the blues” applied to their personal situation in the past two weeks. Ratings on each item were summed, so higher scores indicate more frequent depressive symptoms.

- parenting stress: This 36-item measure asked parents to rate how strongly they agreed with statements such as, “I find myself giving up more of my life to meet my children’s needs.” Ratings on each item were summed, so higher scores indicate greater parenting stress.

- household chaos: This 15-item measure captures the level of confusion and disorganization in a family’s home. Parents were asked to rate how much statements such as, “we almost always seem to be rushed,” applied to their home situation. Ratings were summed so higher scores indicate greater household chaos.

- social support: This five-item measure assessed parents’ sense of connectedness with friends, family, and community by asking how often statements such as, “I feel supported by others,” applied to them. Ratings were summed so higher scores indicate higher levels of social support.

Table 1. Means Values for Demographic and Household Characteristics of EHS Families

| 2018 | 2022 | |

| Respondent race/ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 28% | 23% |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 29% | 31% |

| Hispanic | 38% | 40% |

| Other races, non-Hispanic | 6% | 7% |

| Language primarily spoken to child at home | ||

| English only | 56% | 57% |

| Other language | 19% | 24% |

| Multilingual | 6% | 10% |

| Child developmental disability/delay | 6% | 10% |

| Child gender | ||

| Girl | 48% | 48% |

| Boy | 52% | 52% |

| Child age at survey (months) | 26.11 | 27.32 |

| Household income | $27,775 | $34,710 |

| Number of employed parent figures in household | 1.08 | 1.03 |

| Respondent education | ||

| Less than high school degree | 22% | 17% |

| High school diploma/equivalent | 32% | 32% |

| Less than Associate’s degree | 26% | 22% |

| Associate’s degree | 8% | 11% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 12% | 18% |

| Respondent currently working | 58% | 52% |

| Presence of more than one adult in home | 62% | 62% |

| Program service type | ||

| Center-based | 54% | 59% |

| Home-based | 35% | 33% |

| Combined center- and home-based | 11% | 8% |

Note. Bolded values indicate a statistically significant difference (p ≤ .05) in means between years. The values presented above are weighted to be nationally representative of children and families enrolled in EHS in 2018 and 2022.

FINDINGS

First, we examined whether there were demographic differences between EHS families in 2018 and 2022.

In 2022, EHS served families who were demographically similar to EHS families in 2018, with only a few notable differences. For example, the number of children identified by their caregivers as having a developmental disability or delay increased by two thirds, from 6% in 2018 to 10% in 2022. There was also a significant increase in the educational attainment of caregivers, with fewer caregivers reporting having less than a high school degree, and the number reporting having a bachelor’s degree or higher rising by half in 2022 compared to 2018.

Next, we looked to see if there were significant differences in the stress and well-being of EHS families in 2018 compared to 2022, controlling for child and family characteristics.

EHS families generally experienced higher stress and poorer well-being after COVID-19 than before. In particular, EHS families reported experiencing more depressive symptoms, more parenting stress, and less social support in 2022 compared to EHS families in 2018. However, EHS families saw benefits to their financial situation in 2022 with findings showing that compared to families in 2018, EHS families in 2022 reported higher overall household income and fewer financial strains (see Table 2).

Table 2. Means for Family Stress and Well-Being Indicators in 2018 and 2022

| 2018 | 2022 | Reported Range | |

| Social Support Total Score | 20.95 | 20.37 | 5-25 |

| Financial Strains | .85 | .63 | 0-4 |

| Depressive Symptoms | 4.92 | 7.36 | 0-60 |

| Household Chaos | 10.63 | 10.56 | 0-41 |

| Parenting Stress | 42.14 | 43.44 | 32-90 |

Note. The means presented in this table are from parent-report and are weighted to be nationally representative of EHS families in 2018 and 2022 but are not adjusted for covariates. Bolded values indicate a significant difference in means between years. The reported range includes values for both 2018 and 2022 combined.

Finally, we looked to see if differences in EHS families’ stress and well-being before and after COVID-19 differed based on various demographic characteristics.

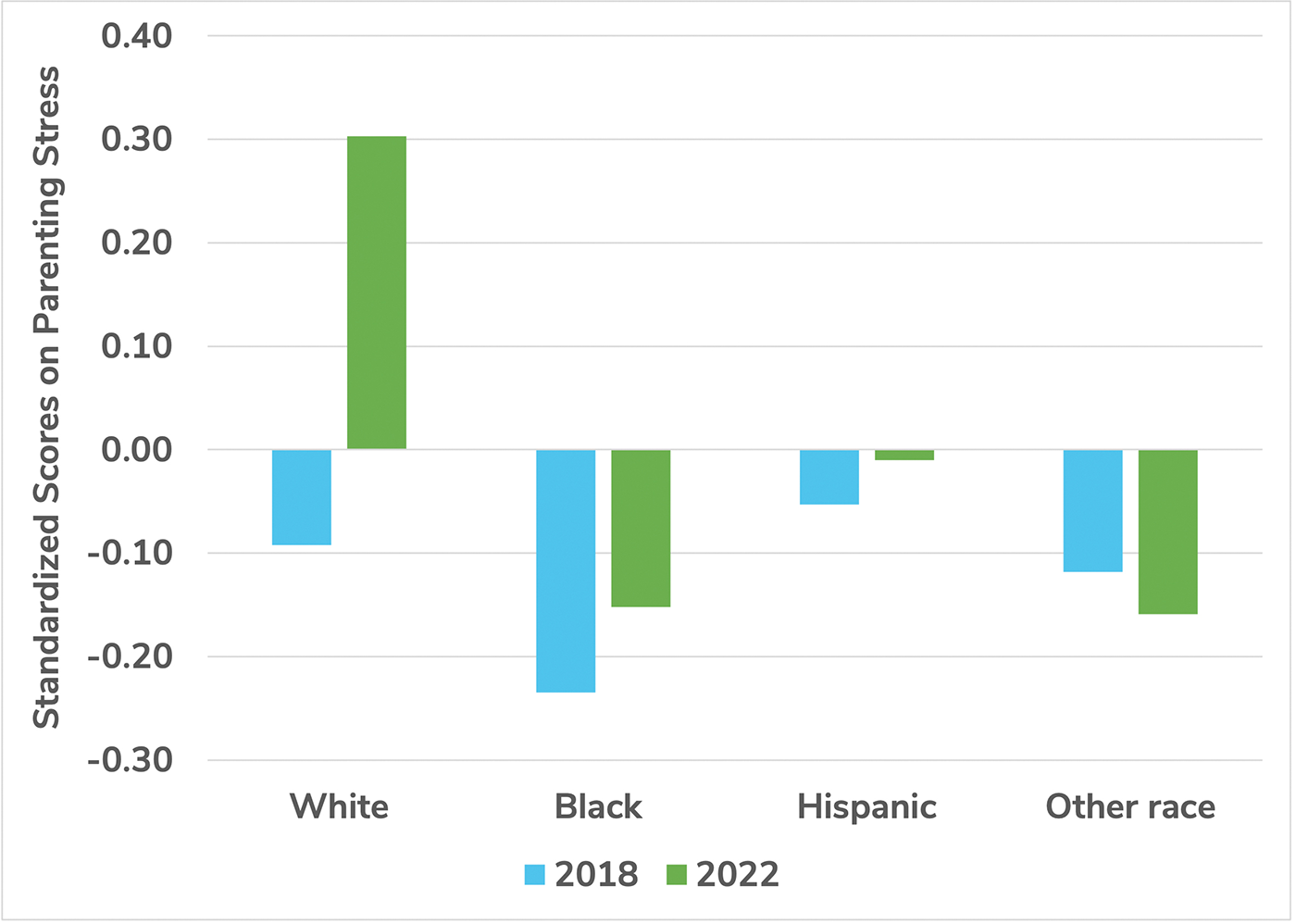

White families experienced the greatest increase in stress and decline in well-being from 2018 to 2022. Specifically, white families experienced a significant increase in reported parenting stress that families who identify as Black or Hispanic did not experience to the same degree (see Figure 1). This finding suggests that the overall increase in EHS family parenting stress in 2022 compared to 2018 was predominantly driven by the changing experiences of white families. Similar trends were found for household chaos, with Hispanic families reporting fewer increases in household chaos compared to those reported by white families. Additionally, Hispanic families reported a greater increase in social support between 2018 and 2022 compared with white families.

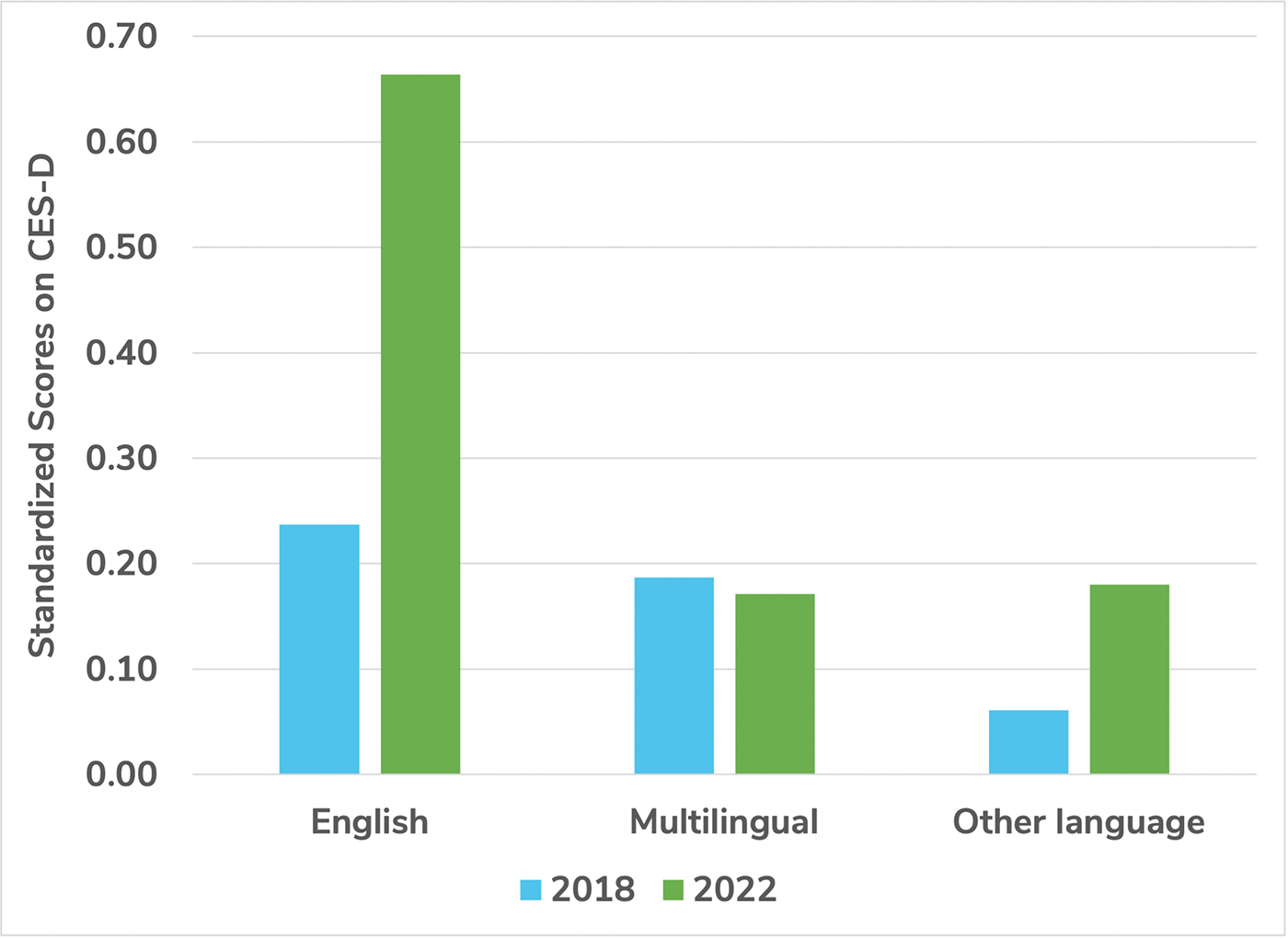

Caregivers who only speak English to their children fared the worst in terms of stress and well-being after COVID-19 compared to before. For example, caregivers who predominantly spoke a language other than English to their child at home reported fewer depressive symptoms, less household chaos, and less parenting stress compared to families who only spoke English in 2022 compared to 2018 (see Figure 2). Caregivers who reported speaking to their child equally in English and another language in the home also reported fewer depressive symptoms compared to English only households in 2022 compared to 2018.

Together, these findings highlight important differences in the stress and well-being of EHS families before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, families generally fared worse on their stress and well-being after COVID-19. While EHS families were demographically similar in 2018 and 2022, Hispanic families and those who spoke a language other than English at home fared better than white and English-only families post COVID-19.

These findings may reflect unique cultural strengths within the Latine community. For example, Boyer and colleagues (2023) found that Latine families may experience greater family cohesion in times of economic stress, which may have buffered against some of the COVID-19-induced stressors. Additionally, there is some evidence that despite the severe challenges imposed by the pandemic, some Latina mothers appreciated the additional time they were able to spend with their children, which may have served as a buffer against other stressors (Bruhn, 2023).

Figure 1. EHS Parenting Stress in 2018 and 2022 by Race/Ethnicity

Note. The change in parenting stress scores between 2018 and 2022 was significantly greater for white respondents than Black and Hispanic respondents.

Figure 2. EHS Parental Depressive Symptoms by Primary Home Language

Note. The change in depressive symptom scores for families with English as their primary language between 2018 and 2022 was significantly greater than for those who identified as multilingual and other language speakers.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Researchers

Continue to conduct research that sheds light on how families are faring after the COVID-19 pandemic and shutdowns. The pandemic and its aftermath led to dramatic shifts in American society that may have profound impacts on family functioning. Understanding families’ stressors and needs, as well as their strengths, is critical to ensuring programs and policies are meeting the needs of families and young children.

Examine how family situations and programmatic supports shape children’s development in recent years. Although we have an abundance of evidence on how family stressors and supports shape children’s development, and how programs such as EHS can enhance children’s development, much of this evidence comes from research conducted before 2020. Understanding how these contextual factors shape children’s development in current times is needed.

Recognize that families’ strengths and experiences shape how they experience significant events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, in line with prior research, our findings suggest that Latine families in the U.S. may have used cultural strengths as a buffer against pandemic stressors. Understanding how families’ strengths shape their experiences and outcomes is key for future research.

Practitioners

Continue to provide supports to address families’ changing mental health and stress levels, especially for low-income families with young children. As this research and others (American Psychological Association, 2023) show, the aftermath of the pandemic continues to be a challenging time for families. These challenges vary across families, with some being more vulnerable to stress and mental health concerns. Thus, working to understand the unique needs of each family served is vital.

Policymakers

Prioritize investing in supports for families with young children. Families are experiencing higher levels of stress and lower levels of well-being after the COVID-19 pandemic. Ensuring that programs that work directly with families, such as EHS, are able to meet the needs of children and families is key to ensuring healthy child development despite the challenges faced post-pandemic.

Continue planning for future events that may disrupt and negatively impact families. While the COVID-19 pandemic created enormous disruptions to daily life around the world, many other large-scale events could emerge in the future that will pose significant challenges to U.S. families. Developing plans to ensure the consistent delivery of existing supports, such as EHS, and providing new supports as needed, will enable responses that minimize detrimental impacts on children and families.

REFERENCES

American Psychological Association (2023). Stress in America 2023: A Nation Recovering from Collective Trauma. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2023/collective-trauma-recovery

Boyer, C. J., Ugarte, E., Buhler-Wassmann, A. C., & Hibel, L. C. (2023). Latina mothers navigating COVID-19: Within- and between-family stress processes over time. Family Relations, 72(1), 23-39. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12748

Bruhn, S. (2023). “Me Cuesta Mucho”: Latina immigrant mothers navigating remote learning and caregiving during COVID-19. Journal of Social Issues, 79(3), 1035-1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.1254

Duncan, G. J., Dowsett, C. J., Claessens, A., Magnuson, K., Huston, A. C., Klebanov, P., … & Japel, C. (2007). School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1428-1446. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428

Gassman-Pines, A., Ananat, E. O., & Fitz-Henley, J. (2020). COVID-19 and parent-child psychological well-being. Pediatrics, 146, e2020007294. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-00729

Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., & Lewis, K. (2022). Test score patterns across three COVID-19-impacted school years. Educational Researcher, 51(7), 500-506. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X221109178

Love, J. M., Kisker, E. E., Ross, C., Raikes, H., Constantine, J., Boller, K., … & Vogel, C. (2005). The effectiveness of Early Head Start for 3-year-old children and their parents: lessons for policy and programs. Developmental Psychology, 41, 885-901. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.885

Perry, B. L., Aronson, B., & Pescosolido, B. A. (2021). Pandemic precarity: COVID-19 is exposing and exacerbating inequalities in the American heartland. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(8), e2020685118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2020685118

Singletary, B., Schmeer, K. K., Purtell, K. M., Sayers, R. C., Justice, L. M., Lin, T. J., & Jiang, H. (2022). Understanding family life during the COVID-19 shutdown. Family Relations, 71, 475-493. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12655

AUTHOR NOTE

The activities of the Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy are supported in part by a generous gift of the Crane family to The Ohio State University. Correspondence about this work may be addressed to Dr. Kelly Purtell (purtell.15@osu.edu).

The recommended citation for this paper is: Abdul-Masih, M., Purtell, K. M., Ansari, A. (2025). The stress and well-being of Early Head Start families before and after COVID-19: A nationally representative investigation. Columbus, Ohio: Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy & The Ohio State University.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to extend a very special thank you to Rebecca Dore and Jamie O’Leary for brief edits, Janelle Williamson for project management, Michael Meckler for copy edits and dissemination, and Cathy Kupsky for designing this brief.

Crane Center for Early Childhood Research & Policy

The Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy, in The Ohio State University’s College of Education and Human Ecology, is a multidisciplinary research center dedicated to conducting high-quality research that improves children’s learning and development at home, in school, and in the community. Our vision is to be a driving force in the intersection of research, policy, and practice, as it relates to children’s well-being. Crane Center research briefs aim to provide research and insights on issues of pressing concern.