AUTHORS: Shayne B. Piasta, Ph.D.; Rachel E. Schachter, Ph.D.; Kelly M. Purtell, Ph.D; Clariebelle Gabas, Ph.D.; Paige Wernick, M.S.

Early childhood is a critical time to foster young children’s language development because early language skills are essential for later reading and academic achievement (Hjetland et al., 2020; National Early Literacy Panel, 2008; Pace et al., 2019). In particular, children’s experiences in early childhood classrooms may be beneficial for supporting language learning given that children spend a large proportion of their time in care outside of the home (Cui & Natzke, 2021). However, research suggests that the quality of classroom language supportive practices is often low (Dwyer & Harbaugh, 2018; Justice et al., 2008) and efforts to enhance practices have been less successful than anticipated (Dickinson, 2011; Markussen-Brown et al., 2017). As such, a key issue in early childhood education is understanding what aspects of early childhood classroom contexts matter for promoting children’s language learning.

Language plays a central role in our ability to communicate, think, and make meaning of our world as we use language to share and exchange ideas across different social contexts. In this way, language often mediates learning as it is used to process and translate external experiences into internal understandings (Bodrova & Leong, 2012). Language consists of understanding and using not only vocabulary but also syntax (i.e., formation of sentences; Lonigan & Millburn, 2017) and morphology (i.e., meanings of word parts; Lee et al., 2023). Importantly, children’s language development is crucial for reading development, since language-related skills like vocabulary, conceptual knowledge, syntax, morphological awareness, and discourse are strongly linked to reading comprehension (Hjetland et al., 2020; Language and Reading Research Consortium, 2015; Lee et al., 2023; National Early Literacy Panel, 2008).

For this reason, fostering children’s early language skills can prepare them for later reading success. Learning language often involves multiple interactions with others in various social and cultural contexts over time (Gee, 2015; Tomasello, 1992; Vygotsky, 1978). Thus, the language experiences provided by teachers in early childhood classrooms are critical for shaping children’s learning and development.

Previous research suggests that various aspects of early childhood classrooms — including teacher-child interactions, materials, and activities — are related to children’s language learning (Baroody & Diamond, 2014; Fuligni et al., 2012). Moreover, teachers’ use of discrete language supportive practices to guide and scaffold children are also related to language learning. These language supportive practices include vocabulary instruction (Dickinson & Porsche, 2011; Wright & Neuman, 2014), commenting (Barnes et al., 2017), and questioning (Deshmukh et al., 2019; Kurkul et al., 2022). However, there is a wide variation in language learning contexts and opportunities provided to children in early childhood classrooms (Cabell et al., 2013; Justice et al., 2008; Pelatti et al., 2014). In addition, language supportive practices have often been investigated separately from other classroom practices, which has led to a to a gap in understanding how multiple practices come together within contexts and across time to facilitate children’s language learning (Hadley et al., 2023).

ProPELL Studies

STUDY 1: Does preschool language learning predict later outcomes?

- Confirmatory

- Longitudinal correlational study using latent difference scores on language and emergent literacy skills

- See results from the research brief Early Childhood Learning and Children’s Literacy Skills in Kindergarten and Third Grade

FINDINGS

-

- Children’s beginning-of-year letter knowledge, phonological awareness, and language skills predicted their kindergarten readiness literacy and Grade 3 reading achievement scores.

- Gains in letter knowledge, phonological awareness, and language, when considered separately, also predicted children’s kindergarten readiness literacy scores; language gains, however, did not uniquely predict these scores.

- Gains in letter knowledge, phonological awareness, and language did not predict Grade 3 reading achievement scores.

STUDY 2: What classroom factors are associated with preschool language learning?

Study 2A (informed Study 2D)

- Confirmatory

- Longitudinal correlational study using latent language difference scores

- Factors derived a priori from existing literature (e.g., language learning opportunities, curriculum, classroom quality, grouping responsivity, linguistic input

Study 2B (informed Studies 2C and 2D)

- Exploratory

- Determined the 30 classrooms where children made the highest language gains and the 30 where children made the lowest gains

- Qualitative comparison of practices between classrooms

Study 2C (informed Study 2D)

- Confirmatory

- Operationalized qualitative differences among classrooms and coded observations for 100 classrooms

- Longitudinal correlational study using latent language difference scores

Study 2D

- Exploratory and confirmatory

- New teacher sample from classrooms where children made high language gains

- Planning and stimulated recall interviews to understand teachers’ pedagogical

reasoning and related factors

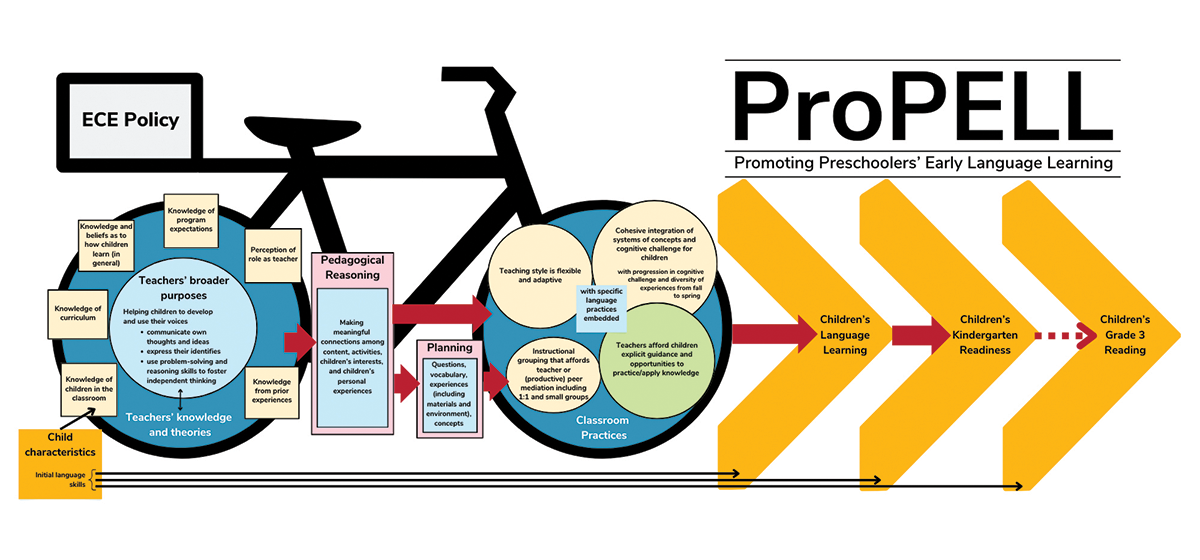

ProPELL CONCEPTUAL MODEL

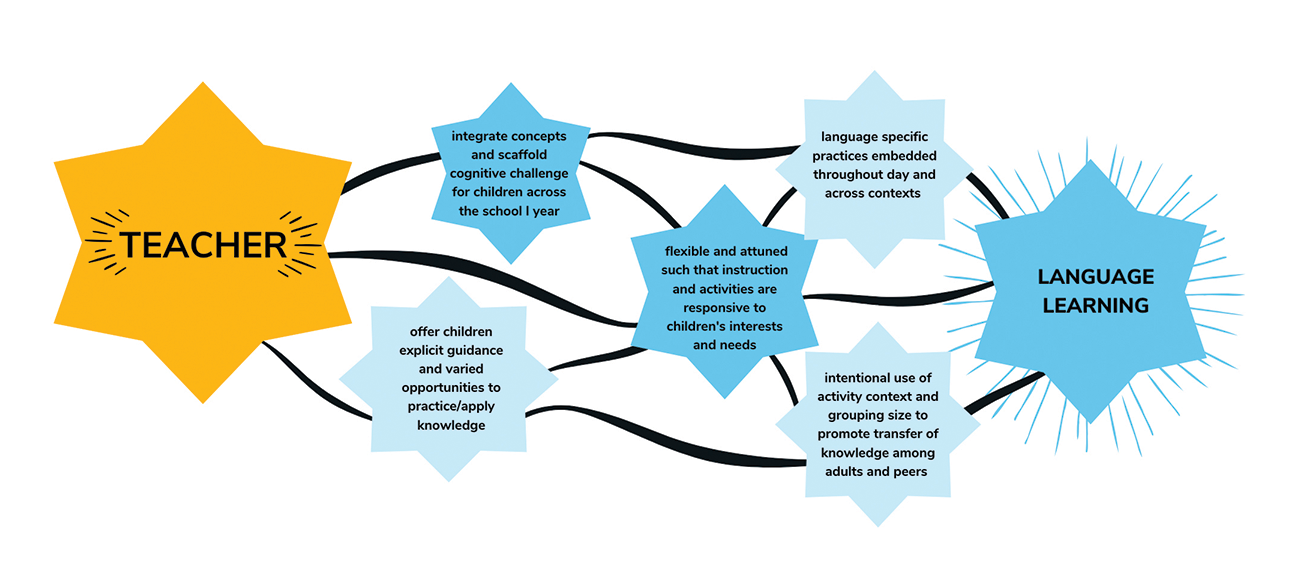

Our conceptual model of ProPELLing children’s language gains (Figure 1) integrates our best evidence on factors that can support language learning in preschool classrooms. Our outcomes of interest are the orange arrows on the right in Figure 1. In Study 1, we demonstrated empirical links between language learning and kindergarten readiness. Although we did not find a direct link from language learning to Grade 3 reading achievement, myriad other studies provide evidence of links between kindergarten readiness and Grade 3 reading (e.g., Justice et al., 2019).

The rest of our conceptual model, depicted graphically as a bicycle propelling forward, focuses on classroom practices that shape children’s language learning and the processes that led these practices to be enacted in the preschool classroom. Some classroom practices, such as teachers affording children explicit guidance and opportunities to practice/apply knowledge, were identified in exploratory qualitative analyses (Study 2b) and found to be correlated with children’s language learning in confirmatory quantitative analyses (Study 2c). Other practices, such as having a teaching style that is flexible/adaptive and teachers’ instructional grouping decisions, were identified in at least two of our studies but require further research to confirm links to children’s language learning. From Study 2d, we were able to understand teachers’ pedagogical reasoning and planning that led to these classroom practices. This decision making, in turn, drew on teacher’s broader purposes as informed by their personal knowledge and theories (see Shulman, 1987). These purposes, knowledge, and theories were informed by teachers’ experiences, understanding of the educational ends, knowledge of their context (including policy), and the children with whom they worked. Importantly, children’s language skills at the beginning of the preschool year were also directly linked to our outcomes of interest.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Our findings and conceptual model highlight several key takeaways regarding children’s language learning in preschool classrooms. These key takeaways align with the graphical depiction of our conceptual model (Figure 1).

1. Language is essential for literacy development and needs to be supported as early as possible. As we show in the conceptual model (Figure 1), not only did preschool children’s language learning predict their kindergarten readiness, but their beginning-of preschool language skills predicted subsequent language learning, kindergarten readiness, and Grade 3 reading achievement (Logan et al., 2024). This is consistent with many studies emphasizing the important role of early language for later reading and comprehension (Hjetland et al., 2020) and for positive learning and development more generally (Burchinal et al., 2020; Ricciardi et al., 2021). The fact that beginning-of-year language skills were a strong predictor of later outcomes suggests that supporting language learning throughout the early years — even before preschool — is critical.

2. No one, specific classroom practice stood out as essential for supporting language learning. Rather, three sets of practices best characterized classrooms where children made high language gains (Cutler et al., 20204; Schachter et al., 2024). These were:

- affording children explicit guidance and opportunities to practice/apply knowledge;

- cohesively integrating systems of concepts and cognitive challenge for children across the school day, with these shifting to more diverse and challenging content and activities over the school year; and

- being flexible and adaptive such that instruction and activities are responsive to children’s interests and needs.

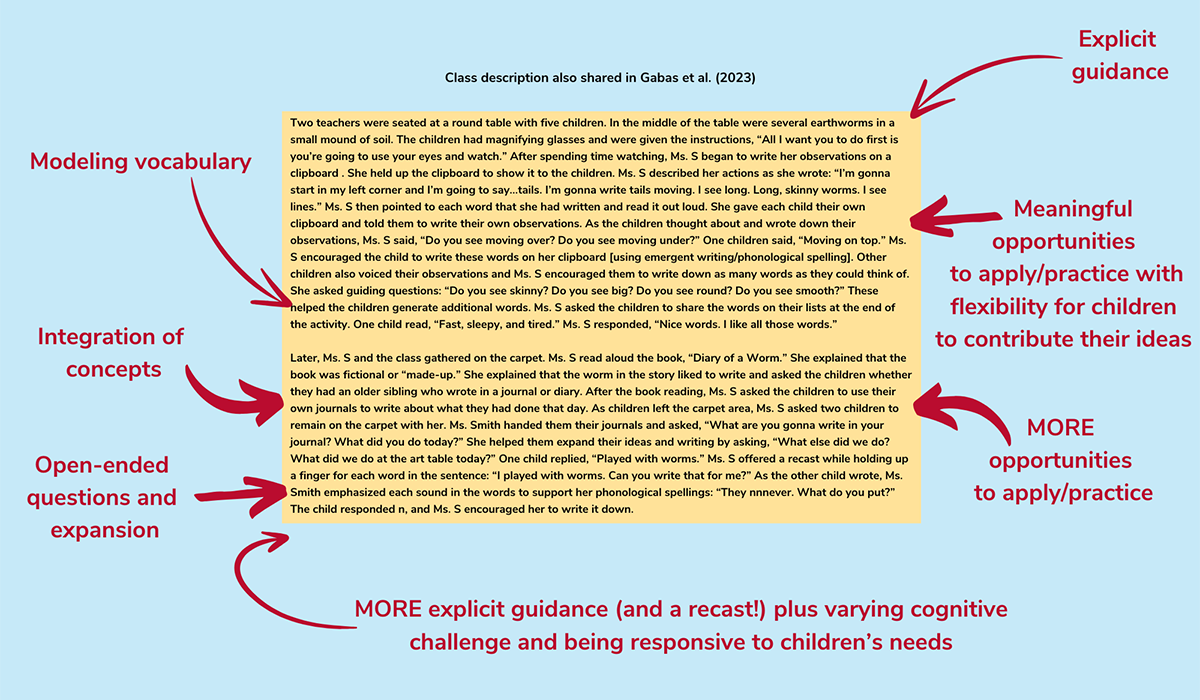

Together, these practices resulted in generative classrooms where children had frequent, sustained, and diverse opportunities to learn, use, and make meaning with language and concepts, as illustrated in the classroom description that we provide (see Figure 2).

These practices were used by teachers in a variety of configurations and adapted to contexts to support children’s language learning. In other words, teachers used differing constellations of these practices to best support the children in their classrooms (see Figure 3). We also found that teachers in these classrooms used small groups or one-on-one time to allow children to interact with and learn from classroom adults and peers. Notably, these practices were not language specific but also supported conceptual knowledge building – learning and integrating information and ideas (Neuman et al., 2016). In fact, we did not find associations between various discrete language-specific practices (e.g., time devoted to teaching vocabulary, inferential language, and other aspects of language; use of sophisticated words; frequency of language facilitating strategies such as repetitions, recasts, and expansion) and children’s language learning. Rather, teachers embedded language-specific practices like providing child-friendly vocabulary definitions and open-ended questions as part of their constellation of practices (see Figure 2).

3. Teachers’ pedagogical reasoning is important for generating language learning opportunities. In classrooms where children made high language gains, we found that teachers’ pedagogical reasoning — their decision-making about practice (Shulman, 1987; Schachter, 2017) — afforded many pathways for supporting children’s language learning. This included planning for language learning opportunities through preparing to teach specific vocabulary, developing questions to facilitate discussion, or organizing the classroom environment/activities to facilitate conceptual development (Gabas et al., 2024). Additionally, during instruction, teachers were often focused on helping children make connections across concepts and their experiences. This provided additional opportunities for language learning as teachers used practices such as expanding children’s ideas and reciprocal conversations (Barnes et al., 2017; Deshmukh et al., 2019). Importantly, because of teachers’ pedagogical reasoning, there were opportunities for language learning across the day — both in planned language-focused activities as well as embedded within the rest of children’s classroom experiences (e.g., in-the-moment teaching). Collectively, teachers’ pedagogical reasoning in planning and focusing on meaning making appeared to be associated with high levels of generative language practices.

4. Having a broader educational purpose to help children find their voice and communicate may ProPELL generative classroom language practices. In our interviews with teachers, we found a consistent belief that their goal as teachers or the purpose of their teaching was to support children in finding their voices (Gabas et al., 2023). This could be through helping children communicate their own thoughts and ideas, express their identities, and use problem-solving and reasoning skills to foster independent thinking and is exemplified in the quote. Teachers developed these views about the broader purpose of education (Shulman, 1987) through their many experiences as teachers, professional learners, and parents. This broader purpose permeated and informed teachers’ pedagogical reasoning in ways that may have facilitated generative language practices and is supported by previous research emphasizing the role of teachers’ beliefs for supporting language instruction (Flynn & Schachter, 2017).

“Gives them confidence to talk in front of friends and to have confidence to talk out loud and to know that it is okay to talk, and you don’t always have to be quiet. And I think that’s a big thing with the language development, is just having that confidence in yourself to be able to do it.”

— A ProPELL preschool teacher on her purpose for teaching language

5. Policy is not directly informing teachers’ purposes and practices around language. Although policies shape multiple aspects of preschool classrooms, they were not primary drivers of teachers’ language learning practices. Teachers were frequently aware of policy factors such as curriculum and assessment requirements and noted the ways in which other policy factors, such as child-to teacher ratios, shape classroom activities. However, they did not directly connect policy factors to their decision making around and implementation of language learning practices. Additionally, our confirmatory analyses did not show direct associations between policy-shaped factors (e.g., child-to-teacher ratio, teacher credentials) and children’s language learning.

Implications for practitioners and early education stakeholders

- Emphasize language as an important early learning and development goal for infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and school-age children

- Encourage and support early childhood teachers to think more explicitly about language learning when planning instruction and activities

- Enhance teachers’ understanding of language as comprising multiple abilities and as a facilitator of overall learning

- Plan for language learning opportunities and incorporate language supportive practices across multiple contexts (e.g., shared book reading, circle and small group time, play) throughout the day

- Increase generative language practices in classrooms that help children use and make meaning with language; generative language practices that provide explicit guidance and opportunities to practice/apply knowledge may be particularly facilitative for children who start off the school year with lower language skills

- Scaffold language learning similarly as for other skills, and increase the complexity of concepts and activities across the school year

- Support language learning in and out of school by connecting families to resources that stimulate rich language environments (e.g., shared reading via Imagination Library and Reach Out and Read, free zoo and cultural passes through the library

REFERENCES

Barnes, E. M., Dickinson, D. K., & Grifenhagen, J. F. (2017). The role of teachers’ comments during book reading in children’s vocabulary growth. Journal of Educational Research, 110(5), 515-527. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2015.1134422

Baroody, A. E., & Diamond, K. E. (2014). Associations among preschool children’s classroom literacy environment, interest and engagement in literacy activities, and early reading skills. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 14(2), 146-162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X14529280

Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. J. (2012). Tools of the mind: Vygotskian approach to early childhood education. In J. L. Rooparine & J. Jones (Eds.), Approaches to early childhood education (6th ed., pp. 241-260). Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Burchinal, M., Foster, T. J., Bezdek, K. G., Bratsch-Hines, M., Blair, C., & Vernon-Feagans, L. (2020). School-entry skills predicting school age academic and social–emotional trajectories. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 51, 67-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.08.004

Cabell, S. Q., DeCoster, J., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2013). Variation in the effectiveness of instructional interactions across preschool classroom settings and learning activities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(4), 820-830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.07.007

Cui, J., & Natzke, L. (2021). Early Childhood Program Participation: 2019 (NCES 2020-075REV). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2020075REV

Cutler, L., Schachter, R.E., Gabas, C., Piasta, S.B., Zimmermann, K., Purtell, K.M., Logan, J.A.R., & Ceviren, A.B. (2024). Generative early language practices in preschool classrooms. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Deshmukh, R. S., Zucker, T. A., Tambyraja, S. R., Pentimonti, J. M., Bowles, R. P., & Justice, L. M. (2019). Teachers’ use of questions during shared book reading: Relations to child responses. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 49(4), 59-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.05.006

Dickinson, D. K. (2011). Teachers’ language practices and academic outcomes of preschool children. Science, 333(6045), 964-967. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1204526

Dickinson, D.K., & Porche, M.V. (2011). Relation between language experiences in preschool classrooms and children’s kindergarten and fourth grade language and reading abilities. Child Development, 82(3), 870-886. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01576.x

Dwyer J. & Harbaugh, A. G. (2018). Where and when is support for vocabulary development occurring in preschool classrooms? Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 20(2), 252-295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798418763990

Flynn, E. E., & Schachter, R. E. (2017). Teaching for tomorrow: An exploratory study of prekindergarten teachers’ underlying assumptions about how children learn. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 38(2), 182- 208. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2017.1280862

Fuligni, A. S., Howes, C., Huang, Y., Hong, S. S., & Lara-Cinisomo, S. (2012). Activity settings and daily routines in preschool classrooms: Diverse experiences in early learning settings for low-income children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(2), 198-209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.10.001

Gabas, C., & Schachter, R. E. (2023, November 15). Teachers’ beliefs about learning: Implications for children’s language development [Paper presentation]. National Association of Early Childhood Teacher Educators Fall Conference, Nashville, Tenn.

Gabas, C., Schachter, R. E., & Bosire, J. (2023). Characteristics of writing events in early childhood classrooms where children made higher language gains. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Gabas, C., Schachter, R. E., & Wernick, P. (2024, April 12). How early childhood teachers plan for language instruction: An exploratory study [Roundtable presentation]. American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, Philadelphia.

Gee, J. P. (2015). Reflections on understanding, alignment, the social mind, and language in interaction. Language and Dialogue, 5(2), 300-311. https://doi.org/10.1075/ld.5.2.06gee

Hadley, E.B., Barnes, E.M., & Hwang, H. (2023). Purposes, places, and participants: A systematic review of teacher language practices and child oral language outcomes in early childhood classrooms. Early Education and Development, 34(4), 862-884. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2022.2074203

Hjetland, H. N., Brinchmann, E. I., Scherer, R., Hulme, C., & Melby-Lervåg, M. (2020). Preschool pathways to reading comprehension: A systematic meta-analytic review. Educational Research Review, 30, 100323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100323

Justice, L., Koury, A., & Logan, J. (2019, May). Ohio’s kindergarten readiness assessment: Does it forecast third-grade reading success? [White Paper]. Crane Center for Early Childhood Education Research and Policy, The Ohio State University. https://crane.osu.edu/files/2020/01/Kindergarten-Readiness-Whitepaper_051619_SINGLES_WEB.pdf

Justice, L. M., Mashburn, A. J., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2008). Quality of language and literacy instruction in preschool classrooms serving at-risk pupils. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 51-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.09.004

Kurkul, K. E., Dwyer, J., & Corriveau, K. H. (2022). ‘What do YOU think?’: Children’s questions, teacher’s responses and children’s follow-up across diverse preschool settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 58, 231-241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.09.010

Language and Reading Research Consortium. (2015). Learning to read: Should we keep things simple? Reading Research Quarterly, 50(2), 151-169. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.99

Lee, J.w., Wolters, A., & Grace Kim, Y.-S. (2023). The relations of morphological awareness with language and literacy skills vary depending on orthographic depth and nature of morphological awareness. Review of Educational Research, 93(4), 528-558. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543221123816

Logan, J. A. R., Piasta, S. B., Purtell, K. M., Nichols, R., & Schachter, R. E. (2024). Early childhood language gains, kindergarten readiness, and grade 3 reading achievement. Child Development, 95(2), 609-624. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.14019

Lonigan, C. J., & Milburn, T. F. (2017). Identifying the dimensionality of oral language skills of children with typical development in preschool through fifth grade. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(8), 2185-2198. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_JSLHR-L-15-0402

Markussen-Brown, J., Juhl, C. B., Piasta, S. B., Bleses, D., Højen, A., & Justice, L. M. (2017). The effects of language- and literacy-focused professional development on early educators and children: A best-evidence meta analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38(1), 97-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.07.002

National Early Literacy Panel. (2008). Developing early literacy. National Institute for Literacy.

Neuman, S. B., Kaefer, T., & Pinkham, A. M. (2016). Improving low-income preschoolers’ word and world knowledge: The effects of content-rich instruction. The Elementary School Journal, 116(4), 652-674. https://doi.org/10.1086/686463

Pace, A., Alper, R., Burchinal, M. R., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2019). Measuring success: Within and cross-domain predictors of academic and social trajectories in elementary school. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 46, 112-125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.04.001

Pelatti, C. Y., Piasta, S. B., Justice, L. M., & O’Connell, A. (2014) Language and literacy-learning opportunities in early childhood classrooms: Children’s typical experiences and within-classroom variability. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 29(4), 445-456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.05.004

Ricciardi, C., Manfra, L., Hartman, S., Bleiker, C., Dineheart, L., & Winsler, A. (2021). School readiness skills at age four predict academic achievement through 5th grade. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 57, 110-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.05.006

Schachter, R. E., & Freeman, D. (2015). Using stimulated recall to study teachers and teaching: A brief introduction to the research methodology. In P. O. Lucas & R. L. Rodrigues (Eds.), Temas e rumos nas pesquisas em linguistica (aplicada): Questos empiricas, eticas e praticas (Vol. 1, pp. 223-243). Pontas.

Schachter, R.E. (2017). Early childhood teachers’ pedagogical reasoning about how children learn during language and literacy instruction. International Journal of Early Childhood, 49, 95-111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-017-0179-3

Schachter, R.E., Gabas, C., Purtell, K. M., & Piasta, S.B. (2024). Generative versus constrained contexts: Differentiating the language learning opportunities in early childhood classrooms. Literacy Research and Instruction. Online First. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2024.2425846

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

Tomasello, M. (1992). The social bases of language acquisition. Social Development, 1(1), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.1992.tb00135.x

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Wiig, E. H., Secord, W. A., & Semel, E. (2004). Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals preschool (2nd ed.). Harcourt Assessment.

Wright, T. S., & Neuman, S. B. (2014). Paucity and disparity in kindergarten oral vocabulary instruction. Journal of Literacy Research, 46(3), 330-357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296×14551474

Zimmerman, I. L., Steiner, V. G., & Pond, R. E. (2011). Preschool language scales (5th ed.). Pearson.

AUTHOR NOTE

The activities of the Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy are supported in part by a generous gift of the Crane family to The Ohio State University.

Correspondence about this work may be addressed to Dr. Shayne B. Piasta. Email: piasta.1@osu.edu.

The recommended citation for this paper is:

Piasta, S. B., Schachter, R. E., Purtell, K. M., Gabas, C., Wernick, P. (2024). ProPELLing Language Learning in Preschool Classrooms. Columbus, Ohio: Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy & The Ohio State University.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank to Kristina Strother-Garcia for brief edits, Janelle Williamson for project management, Michael Meckler for copy edits and dissemination, and Cathy Kupsky for designing this brief.

Crane Center for Early Childhood Research & Policy

The Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy, in The Ohio State University’s College of Education and Human Ecology, is a multidisciplinary research center dedicated to conducting high-quality research that improves children’s learning and development at home, in school, and in the community. Our vision is to be a driving force in the intersection of research, policy, and practice, as it relates to children’s well-being. Crane Center research briefs aim to provide research and insights on issues of pressing concern.