Our Broken Child Care System and How to Fix It, Part 2

This series was originally posted by Early Learning Network. See the original post here.

In this three-part series, Dr. Laura Justice — executive director of the Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy and Schoenbaum Family Center at The Ohio State University (OSU) — surveys the fragmented landscape of child care in the United States, highlighting its vulnerabilities even in the best of times.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, countless families have lost their care, while child care teachers and administrators have lost their jobs. Families have their kids at home. The industry will be dealt a huge economic blow — and then what?

Justice makes concrete, actionable recommendations for the nation, communities and families.

You know it’s a real problem when even the advice columnist is stymied. That’s what happened to The Washington Post’s Karla L. Miller on April 26 when a child care provider explained the difficulty of choosing between filing for unemployment versus accepting her regular pay during the pandemic but working from home on busywork. Speculating that the provider’s regular pay may be less than unemployment would provide, Miller threw up her hands and replied, “I think that calls for us to reexamine how severely and systematically our nation undervalues the work of child care providers.”

Yes, child care programs are a key part of the economic infrastructure, like highways and public transportation, in that it gets people to work. But the child care system is also the nation’s human resources department, developing the nation’s brain trust of the future.

While Miller is perplexed about the chronically low pay provided to child care providers, an even more bedeviling issue is the identity and role of child care providers in our society.

Kyra Swenson, a Wisconsin preschool teacher, recently told The Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, “Our governor proclaimed he was closing schools because we need to protect educators and children and their families.” And yet child care programs were to remain open. “We’re sitting here thinking,” remarked Swenson, “What do you think we are, and what do you think we do?” Those who teach in our nation’s early-learning system, like Swenson, must blanch at the idea of not being viewed as educators but, rather, child minders or baby-sitters.

Educators, researchers and policy experts have long known the nation’s early-learning system, which includes home- and center-based child-care providers as well as public and for-profit preschool programs, was fragile. As discussed in Part 1 of this three-part series, for a number of reasons, the U.S. child care landscape was already on unsure footing before the pandemic arrived. And now it’s on the brink of disaster.

Yes, child care programs are a key part of the economic infrastructure, like highways and public transportation, in that it gets people to work. But the child care system is also the nation’s human resources department, developing the nation’s brain trust of the future.

–––––

Read Part 1 of this series, Before Coronavirus, the U.S. Child Care Landscape Was Already in Crisis

–––––

Read Part 3 of this series, Steps to Sustainability: Fundamental Reforms to Our Systems of Child Care and Early-Learning Programs

Now That We Have Their Attention, What Do We Say?

That’s the urgent problem right now, because of course there are other systems in crisis now, too — health care and agriculture, to name a few — and the nation’s child-care system has been perpetually overlooked. So many facets of American life are breaking down now that it feels impossible to keep track of them all.

But, we literally and figuratively can’t afford to be ignored this time around.

The stakes are high for three reasons.

First, the hard-earned, increasing acknowledgement by many stakeholders of the importance of child care programs and providers is at risk of crumbling. Only in the last decade has the nation come to understand the importance of early-learning programs for stimulating the development and learning of our nation’s youngest citizens. Along with this effort, researchers have increased our understanding of the specialized skill and knowledge that early educators must have to be effective in their work. The pandemic conditions and perspective that child care exists solely as a means for parents to work sidelines this progress.

Second, many of our child care programs may disappear. Because public investment towards early-learning programs, including child care, has long been mediocre, many programs run on very thin margins. If the public doesn’t acknowledge the importance of child care investments to fostering children’s early- and long-term cognitive and social-emotional development, programs will be lost.

Rixa Evershed, early education director at Nature Nurtures Farm in Olympia, WA, told Stella Simonton of Spotlight on Poverty & Opportunity, “Either we’re going to finally get the recognition we deserve or we’re going to implode and cease to exist.” Evershed was talking about her own operation, but she might as well have been referring to the overall picture.“The United States is at risk of losing a large portion of its child care providers,” the Center for American Progress’s Steven Jessen-Howard and Simon Workman write.

In Ohio, where I live, experts anticipate a 45% decline in the supply of child care without help. If we have fewer programs available, we’ll see a surge in child care deserts in which there are too few providers to meet the needs of the families in a community. In such deserts, in which families cannot find reliable, quality care, adults in the household cannot take on gainful employment because they need to care for their children.

Third, as the child care system, or a portion thereof, comes back online, there is great risk that program quality will be compromised. With budget shortfalls across the education sector, early-learning programs operated by school districts will have less money to devote to preschool programs, and programs may go away.

District-affiliated preschool programs often are of relatively high quality, because school districts pay their early educators better wages and benefits and provide professional-development opportunities than many private providers. Child care providers outside of districts already operate on thin margins, and they may have to cut corners to keep their doors open—for example, paying assistants lower wages for fewer hours, which in turn lowers job satisfaction and quality care for children.

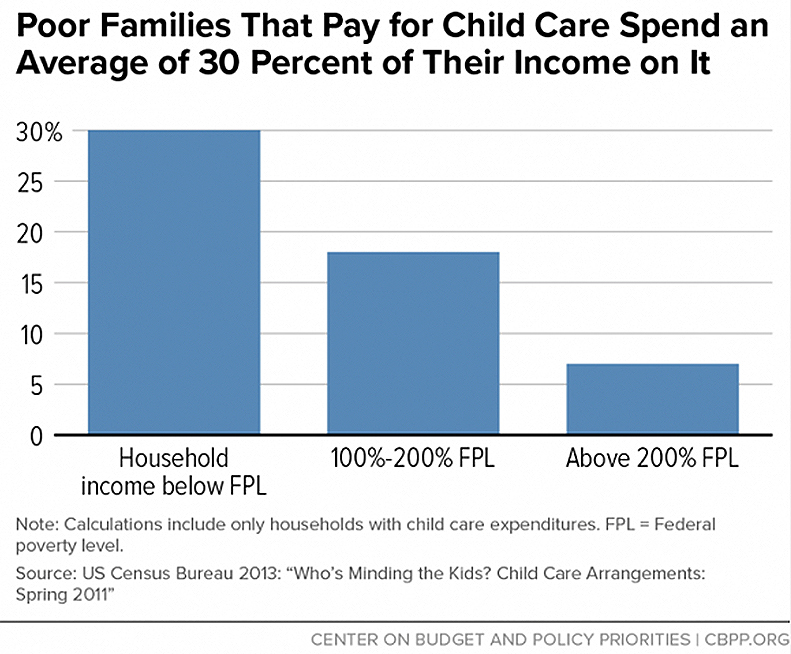

The possibility that we’ll have fewer child care programs, and lower-quality programs when the pandemic is behind us, will undoubtedly affect some American families more than others. Already, low-income families pay more of their salary on child care than those who are advantaged.

It doesn’t require any policy expertise to see who will suffer the most in a possible collapse of the nation’s child care system. It’s the usual list:

- People who earn the least and who don’t have control of the hours they work.

- People who lack transportation or who live in less dense areas where child care centers and family-based child care options are unavailable.

- And above all, women—who are both the primary consumers of this service and the overwhelming workers in the field.

Getting Down to Business

The key to fixing a problem is understanding it. Given the chronic government underfunding of child care in our country, and the likelihood that public-sector funding will shrink in the near-term, it may be necessary to think of the child-like system as a business and to talk about it in business terms. Most importantly, as a business, we need to carefully think about how we motivate early educators, including child care providers, to re-enter these roles.

Julia Barfield, senior manager at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, told the Hechinger Report, “If and when we all go back to work and figure out the new normal, we need to make sure child care businesses are still around, because they are essential for America to get back to work.”

But, it’s more than that. Yes, child care programs are a key part of the economic infrastructure, like highways and public transportation, in that it gets people to work. But the child care system is also the nation’s human resources department, developing the nation’s brain trust of the future. Collectively, this sector serves 21.4 million children who have not yet started kindergarten, and we need to get it right.

Think like a business? People don’t enter the child care professional to get rich; many are motivated by an innate desire to educate and care for young children. However, we cannot continue to mistreat the educators of our nation’s youngest by paying them poverty wages. Paying adequate wages for the work they do needs to be a mandate for the post-pandemic child-care system. But, it won’t be easy. As NAEYC reports, “Even before the pandemic, child care programs were operating on razor-thin margins, and early childhood educators were earning such low wages that nearly half of them were eligible for public assistance.”

Nobody’s suggesting that salaries increase to match bankers and lawyers, but it’s time to question the assumption that food stamps and second jobs are de rigueur for the child care providers in this country. All child care providers should be supported to pursue career-advancement pathways that lead to heightened wages, and there must be parity across all of the child care sector in these wages, regardless of whether one works in a public-school based setting, Head Start, or in for- or non-profit settings.

Chad Dunkley, CEO of New Horizon Academy, a family-owned child care with 70 sites in Minnesota, Idaho, Iowa and Colorado, sounds like a CEO when he talks about child care. Late last year, he told Early Learning Nation, “We have to have small teacher-child ratios. We have to have hours that serve working families. So our schools are open 12 and a half hours a day. But that creates very high labor costs and so we’re unable to pay our teachers what we need and yet we can’t raise tuition rates because parents are strapped.”

As Dunkley’s comments suggest, without significant government investment to right-size the market, the salaries of child care providers will perpetually be strained by market forces, as the majority of parents simply cannot pay any more for the early care and education of their children.

Plans abound for restoring the system. For example, a Blueprint for Action drawn up by National Research Council and Institute of Medicine in 2015 called reinventing how teachers, leaders and other professionals working with children are prepared, credentialed and supported.

We think the reinvention could go even deeper than that. In the next and final installment of this series, we’ll suggest some principles and ideas for the industry to reinvent itself.

GUIDANCE FOR BUSINESSES AND EMPLOYERS FROM THE COUNCIL FOR A STRONG AMERICA

- US Chamber of Commerce Coronavirus Resources and Guidance (comprehensive resource)

- Childcare in the COVID-19 Era: A Guide for Employers (comprehensive resource from IFC)

- Family-Friendly Policies and Other Good Workplace Practices in the Context of COVID-19: Key steps employers can take (UNICEF EAPRO, UNICEF ESARO, and ILO)

- COVID-19: How companies can support society (World Economic Forum)

- COVID-19: Implications for Business (McKinsey & Company)